First Trip to Europe – last updated July 23, 2020

Following the conclusion of the 1902-03 school year in Houston, Harper left teaching and departed for Cornwall, England, located in the southwestern most part of England. William Wendt was at that time painting in St. Ives, Cornwall, having arrived in May of 1903.[1] Wendt had been briefly a student at the AIC, and was at that time an independent artist in Chicago. He would go on to become one of California’s most well-known impressionist painters. He was also, as noted earlier, one of Harper’s mentors. Not much information is available about Harper’s time in Cornwall in 1903, but one, and possibly two, of Harper’s three paintings accepted for the January 28 – February 28, 1904 Exhibition of Works by Chicago Artists were paintings done in Cornwall.

On a prior trip to St. Ives in 1898, Wendt had taken classes with an important landscape painter and instructor, John Noble Barlow, RBA ROI RWA (1860-1917). Barlow also had a connection with another of Harper’s mentors, Charles Francis Browne. Wendt described Barlow in a 1898 letter as “a former colleague of C. F. Browne”[2], the two having likely met as fellow students at the Académie Julian in Paris where Barlow studied from 1887-89.[3] Browne attended in 1887.[4] A photograph reproduced in The Siren, Issue No. 14, October 2017, p. 9, shows five artists in smocks and toques sitting against a wall, two of whom where Browne and Barlow. With these connections to St. Ives, it is hardly surprising that Harper chose to study and paint in Cornwall. He may also have been a student of Barlow’s, although that would have been on his later trip to Cornwall in 1904 since Barlow was out of the country in the summer of 1903.[5]

By the fall of 1903, Harper was in Paris. Since no correspondence or other papers of Harper appear to have survived, what is known of his time is Paris comes from two sources: 1. the letters of Albert Henry Krehbiel, a close friend of Harper’s from the AIC, and 2. a 1904 photograph of a class at the Académie Julian from the Krehbiel files.[6]

The above photograph of the class at the Académie Julian shows Harper seated in the second row, with Krehbiel second to his right. From this photograph it has been assumed that Harper studied at the Académie Julian. Interestingly, however, none of the newspaper or journal articles published about Harper during his lifetime, nor even his obituary, say anything more than that he studied or painted in Paris. Even the Krehbiel letters to not mention Harper specifically in the context of the Académie Julian, although Krehbiel does discuss the competitions sponsored by the Académie Julian in which he and other named students participated. Furthermore, an alphabetical list of students created from documents in the French national archives regarding the Académie Julian[7] contains Krehbiel, Worthington E. Hagerman, Willliam E. Cook, and Leon Lorado Merton Gruenhagen as students of J.P. Laurens, but does not mention Harper. It may simply be that Harper’s time at the Académie Julian was too short to register in one of the surviving records, or that the list of students mentioned above is incomplete. In any event, the photograph does exist and nothing in the other documentation found to date specifically contradicts the conclusion that Harper was a student there from the fall of 1903 to the early spring of 1904.

The Académie Julian was founded in 1868, and by 1903 had become a magnet for foreign art students, including those from the AIC. Numerous well know American artists were among its alumni, including Henry Ossawa Tanner, an American expatriate artist with whom Harper would become acquainted on a subsequent trip to France.[8] The Académie Julian had no entrance requirements, and afforded considerable flexibility to the student, being generally open from 0800 hours to 1800 hours. For a modest sum, a student paid for the privilege of drawing and painting at one of the various locations under the general direction of Monsieur Julian.[9] Students were admitted for a few days, a month, or a year, provided that they paid in advance. The student could select the master under which he wished to work, who would circulate through the class and provide the students criticism once or twice a week.[10] According to one student,

“Students work for the judgment of the master and are enormously elated or depressed by his criticism. He passed from one canvas or board to another and talks rapidly, of course in French, which is an embarrassment to the American who does not understand, although other students are good-natured about translating….Nerves are at high tension. After a criticism, the work for that day usually ends.”[11]

Tanner provided the following rather gloomy description of the Académie Julian in his 1909 writing “The Story of an Artist’s Life”[12] which addressed his early time in Paris:

“The Académie Julian! Never had I seen or heard such a bedlam – or men waste so much time. Of course, I had come to study at such a cost that every minute seemed precious and not to be frittered away. I had often seen rooms full of tobacco smoke, but not as here in a room never ventilated – and when I san never, I mean not rarely but never, during the five or six months of cold weather. Never were windows opened. They were nailed fast at the beginning of the cold season. Fifty or sixty men smoking in such a room for two or three hours would make it so that those on the back rows could hardly see the model.”

We have a fair amount of information about Harper’s time in Paris thanks to the letters of Krehbiel to his fiancé in Chicago, Dulah Evans. Krehbeil had a scholarship from the AIC to study at the Académie Julian[13], and wrote almost weekly wonderfully long and gossipy letters to Evans. Krehbiel and Harper must have been quite good friends since least two thirds of the letters from the 1903-04 school year contain references to Harper. Evans was a classmate at the AIC, and shared the Advanced Life Class with Harper and Krehbiel in the 1899-1900 school year.[14] At this time, Evans was a fairly successful illustrator and freelance commercial artist in Chicago, creating images for the covers of magazines, including Harper’s Bazaar.[15] While we have Krehbiel’s letters to Evans, we unfortunately do not have the full conversation since Evans’ letters to Krehbiel do not appear to have survived.[16] Evans and Harper must also have been friends in addition to classmates as the letters indicate that she made an effort on his behalf in 1904 to sell some of his paintings in Chicago.[17]

Harper began his studies at the Académie Julian in October 1903. About seven other Americans entered at the same time, at least three of whom were “Chicago boys”.[18] Krehbiel, and presumably also Harper, studied under Jean Paul Laurens (1838-1921) as master[19], under whom Tanner had also studied.[20] From Krehbiel’s letters, the Chicago boys stuck together in Paris, with the most frequently mentioned ones besides Harper being Leo Lorado Merton Gruenhagen and Worthington E. Hagerman.

For young men from the U.S. midwest, the Paris of 1903 came as a bit of a shock. In one of his earliest letters from Paris Krehbiel writes:

“I believe that you would enjoy Paris, but I’m not so sure that you would like the people…Enjoyment seems to be the greatest aim of the French people, and apparently they leave no stone unturned in order to find it….Gaiety seems to be their watchword and Sunday the day in which they are able to gratify their desire for amusement.”[21]

Harper and Krehbiel did not forget the Sabbath, however, and attended almost every Sunday evening at 8:15 the “Students’ Atelier Reunions” let by the Rev. Sylvester W. Beach.[22] On November 29, 1903, Krehbiel and Harper attended the atelier, and although snow and sleet covered the pavement Krehbiel reported that “Harper and I went down and we arrived there very early.”

Krehbiel started his time in Paris in a hotel, but once he found an affordable studio lived in that studio. A picture drawn by Krehbiel of his studio shows a sparsely furnished room with a high ceiling.[23] On one side of the room is a high balcony running the length of the 20 ft. room about 4 and ½ ft. wide, with a ladder leading up to what he called his “little home” containing his bed, a washstand and an arm chair. The room was heated by a wood or coal burning stove. This form of studio/balcony arrangement was not uncommon for students, with the stove which was the sole means of heating the room being so small as to be “amusing rather than warming.”[24] Harper most likely had a similarly spare arrangement, particularly given his financial situation. References to joint activities throughout Krehbiel’s letters suggest that Harper’s studio was fairly close in proximity to his.

Like many other American art students in Paris, Krehbiel joined the American Art Association, alternatively referred to as the American Art Club. The American Art Association was organized in 1890 with the backing of a number of prominent Americans, including Rodman Wannamaker, who represented the Chicago Wannamaker firm in Paris.[25] According to the American Art Annual, 1905-6, Vol 5, the Association

“provides not only an unconventional fellowship among artists but also a common meeting-place for students as well as for all interested in the development of American art. The Club’s membership consists of painters, sculptors, architects and students in most of the professions. The Associate membership list contains representatives of nearly all nations, while the honorary membership, headed by our Ambassador and Consul-General, includes most of the leading Americans in Paris.”

The membership entrance fee was $2, with annual dues of $10. The club had a library, a reading room, a parlor, and an athletic room. It was

“a gathering place…to read, eat, smoke and get acquainted with simple fashion. Here the American boys celebrate Thanksgiving with turkeys and plum pudding sent over from New England.”[26]

In other words, it was a place to hang out with fellow Americans.

Unfortunately, there seems to have been some objection from certain of the southern members of the Club to Harper joining the club, and the Chicago boys rallied in his support. In his December 5, 1903 letter, Krebhiel wrote:

“I haven’t been to the club for over a week and from now on that place will see but very little of me….

Hagerman just now dropped in all wrought up over the treatment the club is giving Harper. He had just returned from the club where he had met the chairman of the Membership Com. who had asked him to inform Gruenhagen and myself that there were 13 members who objected to Harper coming into the club. As Gruenhagen and myself had filled out the formal recommendation for Harper’s membership we were advised to withdraw by letter the name of our candidate. It happens however that we don’t intend to do anything of the sort.….We are going to see the finish of this affair and find out whether the club is willing to stand for the petty prejudices of a few.

Some of the southern fellows give me a pain. Their whole aim seems to be to have lots of fun and the thought of study never enters their head. But few of them are here for study as it seems and yet they make the club their ‘hangout’. From what I have observed from their talk I am willing to wager that Harper would discount the entire thirteen in intellect and the other qualities which go to make up a man. Harper is going to make a fight to get in and I am glad of it for there is lots of fight in him.”

In January 1904, Krehbiel, Hagerman, Gruenhagen and Henry Salem Hubbell (another AIC artist painting in Paris) met:

“to discuss Harper’s affair and act on the matter immediately as the Governing board of the club are due to meet during the next week and we were anxious to counteract any move that the opposition might make in having Harper’s name presented to said board. We are now getting us a petition with some forty or fifty names which will be presented to the board without the knowledge of the opposing faction. One named Walhan and Fred Vance are drawing up the petition and will get all the available names possible to signed to it from members who are daily at the club. Tomorrow I am going to canvass the class at Julians and find out how the American boys there feel about it and those that are in favor of the move will be allowed to sign the petition which I will take over later on in the week….”[27]

The next week Krehbiel wrote:

“So far Harper hasn’t broken with the club. Our petition which was signed by some thirty members was laid before the board on Sat. evening and they got rid of the affair by laying it on the table. What the result will be is hard to imagine as the opposition is very strong. It is proposed now that we get up a list of fellows who are willing to resign in case he isn’t admitted. How many are willing to carry their belief that far is hard to estimate. For my party I am willing enough to get out of the affair altogether. Last week I had the petition over at Julians for a couple of days and spent so much time arguing in favor of Harper that I was surprised when my drawing of the week was accepted for the concours.[28] I intend to have Harper with me over at the club whenever I go so if you hear of a good touch fight over here you can figure that we were in it. No one can object to my friend coming to the place in my company.”[29]

Fortunately, no violence occurred, and later references indicate that Harper did on at least one occasion attend an exhibition at the club. This objection to Harper’s membership in the American Art Association is rather curious given that Tanner was himself a member of the club.[30] Furthermore, Wannamaker, one of the founding members of the club and its president, was one of Tanner’s sponsors.

The estrangement between Harper and he club must not have been too deep, however, since Harper listed his address in the 1904 catalogue of the Exhibition of the Works by Chicago Artists of the Art Institute of Chicago, January 28 – February 28, 1904 as 74 Notre Dame des Champs, Paris, which just happened to be the address of the clubhouse of the American Art Association. In any event, Harper left Paris in the spring of 1904, so the club’s membership dilemma became moot.

Excerpts from Krehbiel’s letters show a generally friendly and collegial atmosphere among the Chicago boys. They also reveal Harper’s financial struggles. While at least Krehbiel and Hagerman were supported by AIC scholarships[31] and Browne by an AIC stipend[32], Harper was on his own financially:

December 13, 1903 –

“Now Harper and Gruenhagen are anxious to have me give them composition lessons. Whenever they come in in the evening they usually find me busy in making arrangements and sketching out ideas, so Harper one evening sat down and worked out some likewise. I told him what I knew about it and since then he has been doing them right along. As he says it ‘It is just the thing I have always needed for I learned to walk before I could crawl.’

Harper is a fine chap and always a jolly one to have around. Gruenhagen is very serious but I like him too.“

December 20, 1903 –

“Harper intends to leave for England about the middle of March and may return to the states that same fall unless some good fortune should strike him. Both he and Gruenhagen are going to do some copying in the Louvre in a few days. There are many pictures there of which I would like to have copies so I may do the same sometime before I get through over here….

Today has been another miserable rainy day. Harper and I spent the time until nearly one oclock over in the Louvre looking at pictures until our heads swam. This evening we four went down to the meeting in the Vitti Atelier [Students’ Atelier Reunions]. So far I haven’t missed a Sunday evening there as the talk given by Mr. Beach and the music are too good to miss.”

December 27, 1903 –

“Xmas day was very very quiet here. In the morning I went down to Julians. In the afternoon to [Duvenons?], but I didn’t work with very much heart for I felt the day was too sacred. Still there wasn’t any other alternatives in order to keep from being lonesome. In the evening it was different for Harper, Gruenhagen, an Australian named Geech and myself had a dinner in Gr. Studio.

The day before we had left our order for a cooked goose and even before that I had been to the market and laid in a supply of nuts, oranges, apples, figs and the like. On Xmas day Gruenhagen baked sweet potatoes and made cranberry sauce and we also had our corn cakes with syrup. The dinner was a dandy and lasted from six oclock in the evening until twelve as we had to rest a spell every now and then in order to let things settle. After diner we played ‘hearts’ until very late but I didn’t have any luck at winning which is merely another sign that I’m in love.”

January 3, 1904 –

”Today has been a repeat of yesterday as far as the nice weather is concerned, at least it was nice until a few hours ago when it suddenly commenced to rain in torrents. Harper and I went over to the Pantheon soon after breakfast as he had never seen the decorations there and upon our return we stopped at the Museum Cluny which I had never visited although I had seen and passed by the old ruins in connection with the place many a time.”

January 11, 1904 –

“I don’t know whether Hagerman writes more than once a week to his lady. Between you and me, it appears that Hagerman is rather a fickle chap for he is always talking of some ‘stunning girl’ whom he has just met and she is inevitably in his eyes a ‘pearl’. No doubt the girl in Oshaloosa is much to [sic] good for him, but it would be hard to have______it that way. Poor Gruenhagen is the only fellow in the crowd who hasn’t a girl it seems for Harper has confessed to leaving one in Texas.”

Unfortunately, there is no further information on the girl that Harper left behind in Texas.

January 24, 1904 –

“You see my English friend Geach

[sic]

advertised in the “Journal” the other day for a young Frenchman to exchange [French] lessons with I and for two days the postal service was compelled to use a wagon in delivering his mail. He picked out two, and Harper got two and out of the bushel of letters he brought me I answered one and the fellow showed up immediately so you see there is no reason why one shouldn’t learn French when there are so many Frenchmen dying “parler” French…

Mr. Geach stopped here (as he thought for a day on his way to Italy) in order to see his friend Harper but that one day has lengthened into nearly three months so well is he satisfied with the little colony of friends he now has here…”

Krehbiel’s January 24 letter continues on with a rather derisive description of the perceived work habit failings of another one of the Chicago boys designated “H” (probably for Hagerman since he is mentioned in the previous paragraph). Krehbiel contrasts this with Harper’s hard work and industry which he seems to greatly admire:

“This is all in the quiet Dulah for I don’t want to have the people at the Institute or the people who are furnishing him with funds find out what little advantage he [“H”] is taking of his good chances.

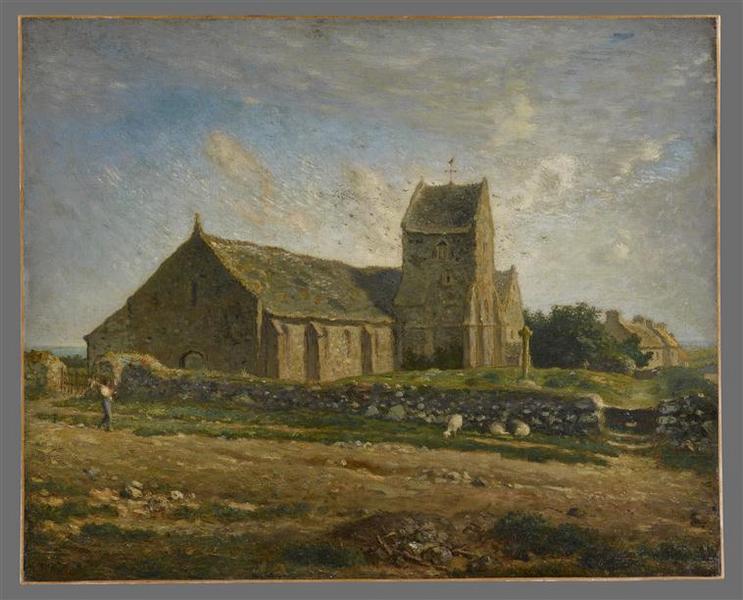

Harper who has no one but himself to depend upon is a different sort of fellow. He is always up about three hours before H, and by the time it gets to be near daylight he is at work. On Mon. and Thur. when he is unable to work at the Louvre he paints all day long in the studio or else goes into the country to make additional sketches. He is busy at the Louvre copying a sunset by Dupré and a landscape with an old church in it by Millet. Harper sent a number of things over for the Chicago Artists Ex, but I haven’t heard whether they arrived in time or whether they were accepted. He and I are going to the Louvre this afternoon and upon our return from there we are going to stop at the club to see the exhibition.”

It is curious that in this letter Krehbiel references Harper’s work at the Louvre, in “the studio”, and in “the country”, but does not mention the Académie Julian. The question again arises as to how much time Harper actually spent at the Académie beyond the time when his picture was taken. Given his financial circumstances, that time may have been quite limited.

A search of the collective catalogue of the state museums of France managed by the Direction des Musées de France[33] (Directorate of French museums) under the French Ministry of Culture shows that in 2019 the Louvre has 21 paintings by Jules Dupré, with two involving a sunset: “Soleil Couchant Aprés l’Orage” (“Sun Setting after the Storm”) and “Soleil Couchant sur un Marais” (“Sun Setting on a Marsh”). Both of these paintings were acquired in 1902, so either could have been the sunset painting that Harper was copying in January of 1904.

The Louvre also has 9 paintings by Jean Francois Millet, with 83 in the collection of the Musées de France over all. The only painting which appears to a church, “L’Eglise de Greville”, is not currently in the Louvre, although the Louvre is listed as a prior location. This may be the Millet painting referenced by Krehbiel.

Official consent was required to copy paintings in the national museums. To obtain such an authorization, the American student had to obtain a recommendation from the American Ambassador, and present the same to the “Directeur des Musées Nationaux” “who has his office in an upper room of the Louvre, up a wonderous winding staircase which one ascends like a tower.”[34] The Directeur would give a general permission to copy in the galleries of the Louvre, the Luxembourg, and other venues, and then a special permission for specific paintings. No payment was required for the permissions or for the gallery entrance, but a student did need to pay the guardian of the museum who provided an easel and stool, and took care of the canvasses when the student was not actively painting. One student reported that:

“It is awkward to attend to these detail when one does not speak French, and it is somewhat resented by the authorities because it gives them more trouble….There are some pictures so popular that four or five are always waiting for a chance to copy, and they secure first, second and third right to the place in front of canvas. They must watch their opportunity to paint, but must decamp if the person with first permit demands it. The word of the guardian is law when rights are disputed….Velasquez, Rembrandts and Titians, Millet’s landscapes, and Paul Potter’s cattle are favorites with Americans.”[35]

While in Europe, Harper continued to submit paintings for AIC exhibitions. On January 31, 1904, Krehbiel wrote:

“Harper has received a note from Mr. French saying that his pictures for the Chicago Ex. had been entered and now he is anxiously awaiting the news whether or not they were accepted by the jury. If they are hung I hope he will be fortunate enough to dispose of them so that he can remain over here for a longer time. He figures that now he can remain only until summer.”

As noted above, three of Harper’s paintings were in fact accepted for the AIC art exhibition held January 28 – February 28, 1904. There is, however, no indication as to whether those paintings sold. The listing in the catalogue of the Exhibition of the Works of Chicago Artists at the Art Institute of Chicago was as follows:

“Harper, William A.- 74 Rue Notre Dame Des Champs, Paris

82. Cornish upland, Cornwall, England. $100

83. An ilex at St. Cloud, France. $35

84. A West Country slope corner. $50”

That year there were 768 works of art submitted for examination by the jury, with 278 selected for the exhibition. The address referenced was the address of American Art Association/Club in Paris.

By February, the weather was occasionally nice enough for Harper and Krehbeil to sketch out of doors. On February 9:

“Harper and I started out early this morning and went up the Seine and the Morne rivers by boat to Charenton about three quarters of an hour from here. Harper has been up there often of late and was so enthused over the place that we decided last night, if it was pleasant, to take our sketching books and spend the day out. For once the day started out fine and the tempirature [sic] was like that of a summer’s day so we enjoyed the ride up the rivers and afterwards over ___ through the various small towns in the vicinity of Charenton. One of these St. Maurce is the birthplace of the painter Eug. Delacroix who died in 1863 and who is represented in the Art Institute by a number of pictures. We only stopped to make one sketch apiece. It was of an old stone mill on a canal near the river. I made mine on paper with the Raeffeli colors and it didn’t turn out very well. Later on in the afternoon the whole country was overrun with people whom the hot sun brought out from Paris so we decided to leave about five oclock before the rush back to the city commenced. “

But on February 14, Krehbiel wrote, “All morning I spent at the Louvre and this afternoon I bummed around with Harper until the rain drove us to cover…”. On February 21, “Harper and I planned to walk to St. Cloud to-day in order to get a little exercise but as usual the weather is too wet to go out…”

Work and weather notwithstanding, Harper and Krehbiel did take time to enjoy themselves, with Krehbiel’s February 21 letter containing the following account of the earlier Mardi Gras celebration in Paris.

“Last Thursday was “Mardi Gras” day here and it was celebrated in the street in rollicking style. It is the Catholic’s last chance to have a good time before Lent and them make the most of their opportunity. Harper and I went down Boulevard St. Michel which starts near here about seven [?] oclock last night in order to see the fun. The sidewalks were crowded with people and as it had been raining hard during the afternoon the pavement was ankle deep with mud. The “Bal Boulliers” [?] is near the end of St. Michel and everywhere could be seen gay crowds in costumes making for that noted dance hall. Harper & I found it rather difficult getting through the crowds and every now and then we would run into a blockade and have to stop. A gang of students would get a couple of girls in a circle and keep them there by running around and round and all the time singing a song. Then after the girls had been thoroughly kissed they would be permitted to go on their way. It is customary to throw “confetti” at each other on this occasion. The stuff is made of heavy paper, and cut into very small disks and this is thrown by the handful. The girls throw at the boys and vice-versa. Whenever a girl throws a handful of “confetti” in one’s face it gives him license to kiss her provided he can catch her. Harper and myself had enough of it thrown at us but we didn’t enter into the sport. Many men were dressed up as women and the women made up like men. One of the funniest sights I have ever seen took place that evening. One fellow dressed as a woman with a high hat and swell make up made love to all the policemen along the route. Harper and I followed him for quite a ways and almost died laughing to see him approach a policeman. He certainly acted well.”

The disparagement of Hagerman’s work ethic continued in Krehbiel’s February 21 letter, and Harper seems to have concurred with Krehbiel:

“By-the-way do you know that Hagie’s [Hagerman] “belle dame” is going to show up here in Paris on next Sat.?…Hagie says “It is all off with Etaples[36] now” so I imagine that he will extend his summer here in Paris and Harper adds ‘Yes and now it will be all off with work for Hagie’ which may be equally true since he hasn’t taken any very great fancy to work since he has been here.”

In his letter of January 24 (see above), Krehbiel discusses Harper painting in “the studio” when he is unable to paint at the Louvre. It is not clear in this instance whether the referenced studio belongs to Harper, or whether it might mean another venue, such as the Académie Julian. Krehbiel’s February 28 letter, however, makes it clear that Harper does have his own studio:

”I started out without my raincoat thinking that I wouldn’t need it but I soon found out that it was rather chilly after all. So I came back here, had a light lunch, and then set out on a three hour and a half tramp which took me over a good part of the southeastern part of the berg and afterwards across the river into northern Paris. By the time I got back to Harper’s studio I was hungry enough to eat a raw bear had one crossed my path. Later on Harper and I went to church, where we met Hagerman and Miss Rosenberger. Their party had arrived about the middle of the afternoon and I think Hagie might have given the poor girl a rest instead of trotting her down to the meeting. She looked very tired and I liked her.’’

Krehbiel not only held Harper in high esteem as a friend and artist, but also sought out his opinion on his art work. As the February 28 letter continued:

“Another composition on which I spend more than a half day represented the old mill at Clarendon. I had Harper see it one afternoon when he dropped in and he didn’t recognize it as the mill we had sketched the other Sunday.

This composition [referring to a sketch in the letter] is also very low in tone and represents the embarking of a barge of grain for the little mill in the ravine. The men in the lower right had corner are on the barge lifting the sacks onto the dock. Others are putting the sacks in a pile while still others are carrying them to the mill.

Harper liked the thing immediately and begged (?) me not to touch it again. However it isn’t what I want as yet, so I intend to work on it until I get it right.”

We are also indebted to Krehbiel for the knowledge that Harper was a good cook. In his letter dated March 12, 1904, Krehbiel wrote:

“It wasn’t until late in the afternoon that I got back here almost supper time. Harper suggested that we have supper with him (Geech and myself) so we chipped in on the expense and had a rousing good meal for Harper is a good cook as well as a painter.

After that we all went to the [Sunday evening] meeting. I did not see Hagie and the lady there this evening although they may have been present in the crowd without my noticing it….”

In that same letter, Krehbiel discussed Harper’s ongoing financial difficulties and his challenges as a “colored man” painting in the U.S.:

“Harper has written to Miss Willard in order to find out whether she will be able to sell some small sketched in oil for him. I have been urging Harper to remain over on this side of the water if he could possibly arrange to do so.

A colored man whether in the north or the south isn’t treated with very much consideration in the states while here it is entirely different. If I were in his place I would go to England (where he likes it) get a small piece of land, which can be had for 25 dollars per year and sketch there until my work would sell.

Harper likes the idea and may carry it out for I don’t doubt but that he will be able to make his living ere long from what he produces.

It is very good of you to give so much time and trouble trying to dispose of his things. I haven’t said anything about it to him for he might be come to [sic] hopeful that some of the stuff would be sold and make his plans accordingly.

I hope that Miss Willard will be able to sell some of the smaller pictures, for I believe they would sell more readily than the larger ones. In the modern buildings the rooms are usually so small that a large picture cannot be seen, so I should think that there would be a demand for little pictures….”

Miss Geneva Willard was on the staff of the AIC, and the exhibition catalogues of the AIC generally referred those interested in purchasing paintings to Miss Willard at “the desk”. There is no report in any of Krehbiel’s letters as to whether or not Evans or Willard had any success in the sale of Harper’s paintings.

In early March of 1904, Charles Francis Browne arrived in Paris after a painting sojourn in Scotland, and, according to Krehbiel, “immediately came over to see Harper”.[37] As noted earlier, Browne is one of two individuals identified as mentors of Harper. Browne was both an accomplished painter and an instructor at the AIC, with the AIC providing Browne support of $600 for his time in Europe. Browne’s plans were to remain in France until after the Paris Salon and then return to Scotland. [38]

The Paris Salon was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and every artist and art student in Paris aspired to have a painting “accepted” by the Salon. The Chicago boys were no exception. According to Krehbiel’s letters of March 12 and March 20, Harper submitted a landscape for the 1904 Salon, Krehbiel and Gruenhagens each submitted two paintings, and Hagerman submitted one painting. Browne also submitted a painting. None of the paintings appear to have been accepted, however, as none of the four students, nor Browne, are listed in the “Catalogue Illustré du Salon de 1904”. With regard to the Salon, Krehbiel wrote in his March 20 letter:

“I wish that you could have witnessed what has been going on in this vicinity since the opening of the salon. In whatever direction one would look, one could see “scads” of pictures carried along or being loaded into carts. One never knows really which are artists hacks

[studios]

or musicians until Salon time when they begin to cart out their pictures.

Harper and I passed the Grand Palace to-day, and stopped for awhile to see the many wagons unloading their stuff into the building. The street was full if men carrying or wheeling along pictures and at the long entrance there was almost a blockade of big furniture vans each one pouring its share of pictures into the building.”

At the same time as the Salon was taking place, a competing Salon des Indépendants (Société des Artistes Indépendants) was being held at the Grandes Serres de la Ville de Paris (Cours-la-Reine). The Salon des Indépendants was an annual independent art exhibition established in 1884 in response to the rigid traditionalism of the official government-sponsored Salon. The Salon des Indépendants allowed artists to present their works to the general public directly, rather than through the selective method of the government Salon. According to Article 1 of the By-laws of the organization: “The purpose of Société des Artistes Indépendants—based on the principle of abolishing admission jury—is to allow the artists to present their works to public judgement with complete freedom”. In 1904, 2,395 works were exhibited.[39] The modern avant-guarde paintings, however, were often ridiculed by critics. The American students were no different, and Harper in particular seems to have failed to appreciate the contemporary trends in art. As Krehbiel wrote on March 20:

“Some blocks further on is a large glass palace facing the river. A large sign says that the Independent Artist Exhibit is within. I saw the sign last Sunday from across the river while with the Julian mob and since then I have heard people tell of what a frightful exhibit it really was. So I told Harper if he would go along I’d pay his way in.

Well it was a regular circus! Just imagine some fifteen hundred pictures any of which could have been improved upon by your Saturday students. Painted in all the colors of the rainbow and in every manner imaginable. Harper and I saw the thing from start to finish and it proved to be such a treat to Billie that we remined there an hour and a half. Every few minutes Harper would double up with laughter and I had to warn him continually lest he might offend the artist if he chanced to be near. Harper said that a man who had gaul [sic] enough to think that stuff of that kind was art ought to be offended. Which happened to be pretty near true in this case. The independent artists are certainly a lot of independent individuals. They have no jury. Membership can be had by paying five francs which will entitle you to send in five pictures which are hung without fail. I’m thinking of going it before long.

I hadn’t expected to find things quite as bad as they were. I had imagined when people told me of the show that they might be a little prejudiced and that perhaps one would find there after all some “artistic daubs” which are often preferable to so called finished pictures. But in this I was mistaken for by far the greater part of the stuff looked like childrens work.

We ran across Hubbell in the exhibit. He shook his head and said that he couldn’t understand it at all – then he added that Paris is certainly the art center for it is only here that such stuff would be allowed in a show.”

The letter went on to discuss Harper’s travel plans with Browne and a possible employment opportunity:

“Harper and Brown[e] are going down to a place near Barbizon in a few days where they will very likely stay until the opening of the Salon on the first of May. After that Harper might go to England and Brown[e] shall return to Scotland.

By-the-way, Harper has been offered a position as instructor in drawing in Booker T. Washingtons school down in Alabama. He rather likes the idea of attaching himself to that institution in case he will be allowed sufficient time as that he can keep at his painting. That school is being backed pretty heavily by wealthy men and it may be that if he should go there it would be the means of his meeting some rich “bugger” who thought well enough of his work to launch him onto a carreer [sic].

You know that Tanner has been backed for a good many years by Mr. Wanemaker [sic] and just recently I heard it said that some wealthy Chicago woman has made it possible for Hubbell and his family to remain over here for the last seven years.

Harper tells me that Wm. Wendt has been backed for years by a wealthy Chicago doctor so one begins to see why some are able to hold out until success strikes them while others fall by the wayside….

I saw the things Hubbell sent to the Salon. There was a reception at his studio last Wed. afternoon from two until four. Harper and I went over together and staid [sic] some time.”

The reference to Booker T. Washington’s school was to Tuskegee University, in Tuskegee, Alabama. There is no evidence, however, that Harper ever did teach at Tuskeege. All indications from subsequent newspaper articles and publications are that he returned to the Chicago area at the 1904, and none appear to contain references to Tuskegee.

Harper and Browne left Paris together in mid-March. On March 27, Krehbiel reported that:

“Harper left last Tues. so that since then I haven’t been in their room. While he was still here he and I were together often in the evenings for I like Harper who manages to keep a cheerful disposition even in the face of adversity. I wish I were built on the same principal but I am afraid that I am not. However whenever I get with a person who is in good spirits I usually contract the same disease and likewise forget my troubles. Perhaps it was for this reason that we were together so often. Anyway I have missed him this week.

Harper and Chas Francis Brown[e] went down to a little burg somewhere south of here last Tuesday morning. In all likelihood he will remain there until the show opens here in May….”

This letter, like others, suggests that Harper lived fairly near Krehbiel, but his exact address is not known. Likewise, it is not clear who Krehbiel meant when referring to “their room”. The phrasing suggests that Harper was sharing a room, but his roommate is not specifically identified in any of the letters. Clearly, Harper and Krehbiel were close friends, and Krehbiel held him in high regard.

Although Krehbiel cites the town of Barbizon located in the Seine-et-Marne department of north-central France as the pair’s destination, Harper and Brown also painted in Montiguy, a village situated on the banks of the Loing River, likewise located in Seine-et-Marne. Two of Harper’s paintings listed in the catalogue of Exhibition of Works by Chicago Artists at the AIC January 31 – February 26, 1905 were painted in Montigny: “Early afternoon, Montigny, France” and “Banks of the Loing, Montiguy, France”. The Loing is an 88 mile tributary of the Seine running through central France. Montigny (or Montigny-sur-Loing as it is now called) is a small commune or township on the Loing located south of Fontainebleau, about 60 miles southeast of Paris. It is not known how long Harper stayed in Montiguy, but according to the catalogue for the “Exhibition of Paintings and Sketches by Charles Francis Browne” held at the AIC in December of 1904, Browne painted in Montiguy during the months of March, April and May of 1904.

Following his stay in the French countryside, it appears that Harper returned to Cornwall. William Wendt was in back in Cornwall after a trip to the continent beginning in March and remained there through the summer[40], so it is logical that Harper returned to continue his painting with Wendt. In any event, seven of Harper’s nine paintings listed in the catalogue of Exhibition of Works by Chicago Artists at the AIC January 31 – February 26, 1905 were painted in Cornwall. The full listing from that catalogue is as follows:

“Harper, William A. – Art Institute, Chicago

100. Morning, midsummer, Cornwall, Eng. $150

101. Early afternoon, Montigny,, France. $150

102. The hedgerow, Cornwall, Eng. $100

103. Eventide, Cornwall, Eng. $50

104. Banks of the Loing, Montigny, France $100

105. The potato field, Cornwall, Eng. $35

106. Lobbs house, Cornwall, Eng. $35

107. Grey day, Cornwall, Eng. $35

108. Quiet morning, Cornwall, Eng. $35”

On October 24, 1904 Harper set sail on the S.S. Parisian from Liverpool, England, travelling in steerage class, arriving at the port of Montreal on November 6, 1904.[41] The ship’s manifest lists Harper as an artist, whose final destination is Chicago “home of Art Institute”, and notes that Harper had all of $15 in his possession. [Attach]

[Discuss influence of exposure to

tonalism in Cornwall and the Barbazon school on Harper?]

[1] “American Artists in St. Ives” by David Tovey, https://www.stivesart.info/american-artists-in-st-ives/ . Documents on the Life and Art of William Wendt, by John Alan Walker, 1992, pg. 47.

[2] “John Noble Barlow (1860-1917) – A Centennial Tribute”, by David Tovey, The Siren, Issue No. 14, October 2017; p. 10, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ht830l9nFh9xzFRh_MfAJI7APQJprxcr/view.

[3] https://sites.google.com/site/academiejulian/b-1/john-barlow.

[4] https://sites.google.com/site/academiejulian/b-1/browne-1.

[5] “John Noble Barlow (1860-1917) – A Centennial Tribute”, by David Tovey, The Siren, Issue No. 14, October 2017; p. 9, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ht830l9nFh9xzFRh_MfAJI7APQJprxcr/view.

[6] Albert Krehbiel papers. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[7] See: https://sites.google.com/site/academiejulian/home.

[8] Henry Ossawa Tanner was considered the foremost “Negro” artist of the time. Obituary, Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago, Vol. 4, July 1910, p. 11.

[9] Henry Ossawa Tanner, American Artist, by Marcia M. Mathews, 1969, p. 57.

[10] The Julian Academy, Paris 1868 – 1939, “Spring Exhibition 1989”, essays by Catherine Fehrer, Shepherd Gallery, N.Y.

[11] A Reading Journal Through France, “Art Life in Paris”, by Fanny Rowell, Chautauquan 30:408, January 1900.

[12] “The Story of an Artist’s Life, by H.O. Tanner, The World’s Work, Vol. XVIII, May to October, 1909, p. 11770.

[13] Krehbiel – Life and Works of an American Artist, by Robert Guinan, 1991, p. 5.

[14] Circular of Instruction of the School of Drawing, Painting, Modelling, Decorative Designing and Architecture for the AIC, Catalogue of Students for 1899-1900.

[15] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dulah_Marie_Evans.

[16] Information courtesy of the Krehbiel family grandchildren. For more information on Krehbiel, see the website: https://www.krehbielart.com/index.htm .

[17] Albert Krehbiel, (March 12, 1904) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[18] Albert Krehbiel, (October 8, 1903) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[19] Albert Krehbiel, (October 8, 1903) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[20] Henry Ossawa Tanner, American Artist, by Marcia M. Mathews, 1969, p. 65.

[21] Albert Krehbiel, (October 25, 1903) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[22] Albert Krehbiel, (November 29, 1903) and (December 20, 1903) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[23] Albert Krehbiel, (November 29, 1903) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[24] A Reading Journal Through France, “Art Life in Paris”, by Fanny Rowell, Chautauquan 30:406-7, January 1900.

[25] Henry Ossawa Tanner, American Artist, by Marcia M. Mathews, 1969, p. 61.

[26] A Reading Journal Through France, “Art Life in Paris”, by Fanny Rowell, Chautauquan 30:406, January 1900.

[27] Albert Krehbiel, (January 3, 1904) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[28] Weekly competitive exams on Sundays at the Académie Julian.

[29] Albert Krehbiel, (January 11, 1904) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[30] Henry Ossawa Tanner, American Artist, by Marcia M. Mathews, 1969, p. 61.

[31] Krehbiel – Life and Works of an American Artist, by Robert Guinan, 1991., p. 5.

[32] Albert Krehbiel, (March 12, 1904) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[33] http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/documentation/joconde/fr/recherche/rech_libre.htm.

[34] A Reading Journal Through France, “Art Life in Paris”, by Fanny Rowell, Chautauquan 30:410, January 1900.

[35] Ibid, p. 410-12.

[36] Étapes was a small artist colony and fishing port on the north bank of the Canche river, on the train line between Paris and London. Henry Ossawa Tanner had a home nearby (in addition to his Paris apartment).

[37] Albert Krehbiel, (March 12, 1904) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[38] Albert Krehbiel, (March 12, 1904) “Letters of Albert Krehbiel”. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

[39] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Société_des_Artistes_Indépendants

[40] “American Artists in St. Ives” by David Tovey, https://www.stivesart.info/american-artists-in-st-ives/. Documents on the Life and Art of William Wendt, by John Alan Walker, 1992, pg. 47.

[41] List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the U.S. Immigration Officer at Port of Arrival, National Archives and Records Administration